The Earl of Dysart

Found in: The History of the Study of Medicine in the British Isles

Now strictly speaking this is a mark in a book, and not exactly a bookmark, but I have decided to expand the remit. This dedication is found in a copy of The History of the Study of Medicine in the British Isles (1908), by Sir Norman Moore, a famous physician and medical historian, but not a fan of short book titles.

The Earl of Dysart is an extant peerage of Scotland, first created in 1643 by Charles I for his whipping-boy-turned-adviser William Murray. The practice of having a whipping boy was apparently intended to bring rogue princes to heel, who themselves could not be subject to corporal punishment. This practice seems to have had limited success in some cases, including Louis XV of France, who persisted to neglect his studies despite the beatings to his proxy. Nevertheless, the ear of the king and a peerage are not insignificant rewards. It is worth noting that the concept of the whipping boy was seized on in literature, and there is a grey area surrounding how much of the practice was fact over fiction.

Ham House, Richmond. One-time seat of the Earls of Dysart, donated to the National Trust in 1948 by Sir Lyonel Tollemache. Credit: By Stevekeiretsu - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62362841

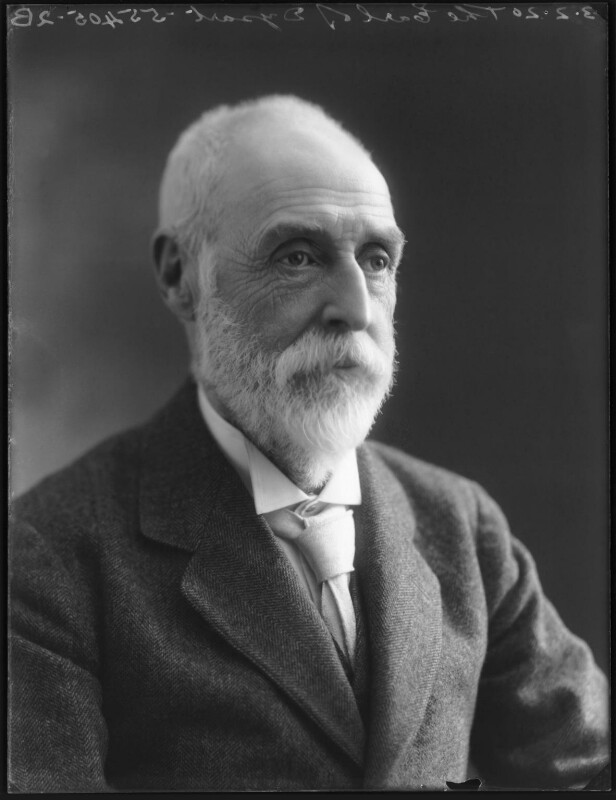

In 1908 the title was held by William John Manners Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart, the last Earl to live in their seat of Ham House in Richmond. Although partially sighted since birth, he apparently led an active life, but it may have made the enjoyment of The History somewhat difficult.

William John Manners Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart. Credit: National Portrait Gallery CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

He was fond of music, being president of the London Wagner Society from 1884 to 1895, which culminated in commissioning a controversial biography of Wagner by Ferdinand Praeger, which ultimately led to his resignation. The book was published after Praeger’s death, who apparently had fabricated the content of Wagner’s letters, drawing criticism from a number of sides, including Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a British-German philosopher who played an influential role in what was to become Nazi racial policy.

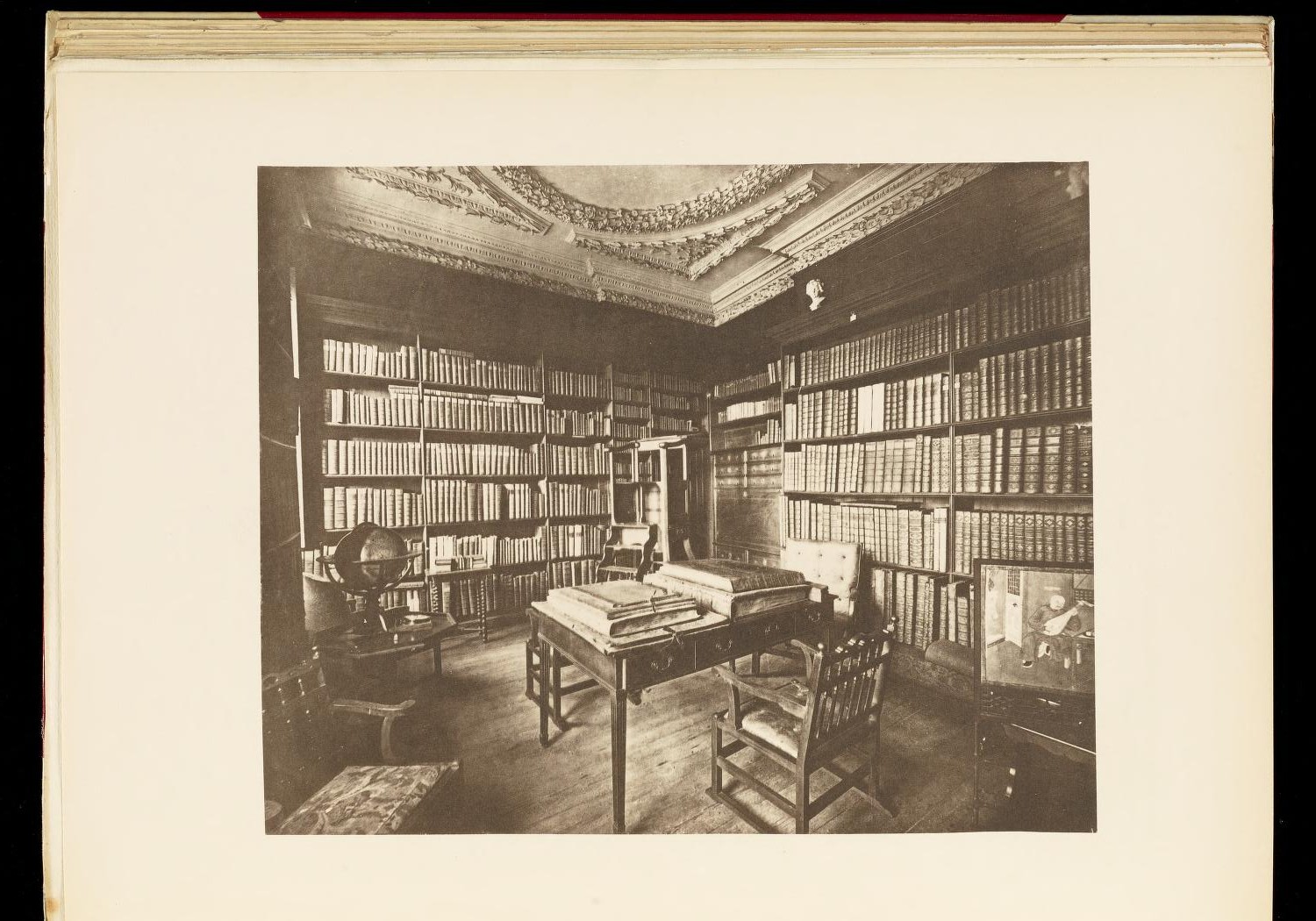

So far I’ve found no connection between Sir Norman Moore and our Earl, or even to medical history. However, the library at Ham House was prodigious, described as ‘perhaps the smallest of the libraries of Europe, and yet in proportion to its size it contains books of greater value than any other.’1

The library at Ham House in 1904. Credit: Ham House, its history and art treasures - archive.org

Following William’s death in 1935, the house passed to his cousin, Sir Lyonel Tollemache, who donated it to the National Trust in 1948, in part due to its difficult upkeep in the post-war period. The majority of the books were sold in 1938, with much of the remainder following suit after the Second World War.

As to my book, it is impossible to say whether it was read by its original owner. It’s littered with pencil annotations, underlining, and enthusiastic exclamation marks, including in the dense sections of latin prose. So I do like to imagine him sitting there in the library of Ham House, scrawling ‘Retention of Urine!!!’ next to a description of the health of James I.

-

Roundell, Charles, et al. Ham House: Its History and Art Treasures. United Kingdom, G. Bell and sons, 1904. ↩︎